READ THIS: Winter of the World by Ken Follett Our Coverage Sponsored By Stribling and Associates

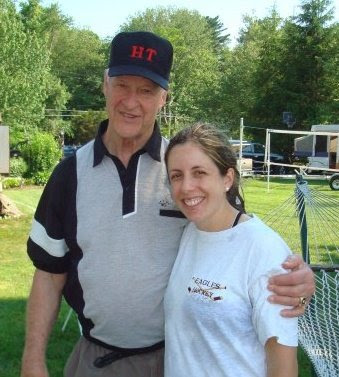

Peachy Deegan and Ken Follett

For over 30 years, Stribling and Associates has represented high-end residential real estate, specializing in the sale and rental of townhouses, condos, co-ops, and lofts throughout Manhattan and Brooklyn, and around the globe. Stribling has more than 200 professional brokers who use their respected expertise to provide personalized service to buyers and sellers at all price levels. A separate division, Stribling Private Brokerage, discreetly markets properties over $5 million, and commands a significant market share in this rarified sector of residential real estate. Stribling is the exclusive New York City affiliate of Savills, a leading global real estate advisor with over 200 office in 48 countries.

Check out their listings:

What makes this book review different from most others is Peachy got to meet the author, Ken Follett, on his only North American book signing for Winter of the World at the New York Historical Society, one of our favorite places:

It is the sequel to Fall of Giants:

which we also loved, and second to come out in this knockout trilogy that will have any lover of historical fiction or books alone terribly wowed! This is one of the most fun ways to learn history-by reading Ken Follett, and that's coming from someone who has a BA in it. You never stop learning. And, if you're a believer in the maxim of what is meant to be happens, you'll love this book. The approximate 1,000 pages absolutely fly by, and you'll be so sucked in you won't be able to do anything else-in fact, you should all start reading this as we go through Sandy it will be a great distraction!

You'll be immediately delighted to reconnect with the characters we know and love from The Fall of Giants and get to know their children now! Follett has amazing insight into the human condition and shows through character development that people show you who they are and they don't often change-they are intrinsically who they are (Lev!). On the contrary to that, we love characters that exhibit the trait of being able to rise to the occasion, as Daisy does on page 398.

For someone that lives in present day Manhattan, you will have to put yourself in the era of WWII with all of its lack of open-minded thinking, from race to religion to sexual orientation-they have it all here. It will evolve your perspective to see how Follett brilliantly captures each scenario in a historical context, showing readers how the world has really evolved since and it will give you greater gratitude for the world we live in today. The German families and what goes on in them and their immediate society will give you insight into Nazi behavior and a point of reference as to how such horrid ideas could be lived out.

We also love how Follett can flawlessly weave past world leaders into his storyline. As they speak and interact with the characters we know firsthand from Follett from close or afar, the context of the story of Winter of the World is indeed heightened. And it is also interesting to see what characters predict-Senator Dewar thinking we would not go to war against Japan..the Pacific Theater we really related to as Peachy's grandfather was a WWII decorated Marine veteran who earned the purple heart-he was in Guam, Guadacanal, Bougainville: in fact, he was in the Third Marine division referenced on page 743...we liked Follett's military history he included and especially liked the maps in the front and back covers of the book.

The cultural significance of America as it emerged as a world power also made us love the book, and the Coca Cola references reminded us of the fantastic book by our late friend Connie Hays.

Most of all, the humanity that each character evokes regardless of their country, sex or religion will warm your heart as we all know-life is both good and bad, and we all love the triumph over evil. We absolutely cannot wait for the third installment.

Whom You Know Highly Recommends Winter of the World by Ken Follett. It is a masterpiece.

***

Now, in WINTER OF THE WORLD, Follett plunges his vivid characters into the equally turbulent events of the 1930s and ’40s and a world shaken to its core by tyranny and global conflict on a scale previously unimagined.

Berlin in early 1933 is in upheaval. Germany’s newly appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler, is strengthening his grip on power. His National Socialist party doesn’t yet have an overall majority in the Reichstag—the German parliament—so, for the present, the other political parties are able to restrain Nazi excesses. But it’s only a matter of time. The rule of law is rapidly being replaced with bullying, beating, and the intimidation of political opponents. Fascism is on the rise, in Germany and elsewhere, and no one will escape unscathed.

WINTER OF THE WORLD: Book Two of Tthe Century Trilogy (September 18, 2012; Dutton; $36.00) picks up right where the first book left off as Follett’s five linked families struggle to navigate a time of enormous social, political, and economic turmoil. It is a pivotal span of years that includes the Great Depression and the rise of the Third Reich, the Spanish Civil War and the great dramas of World War II, the explosions of the American and Soviet atomic bombs, and the beginning of the long Cold War. Bringing us into a world we thought we knew, but now will never seem the same again, Follett’s saga of unfolding drama and intriguing complexity seamlessly combines historical background and real-life events that are brilliantly researched and rendered, fast-moving action, and memorable characters rich in nuance and emotion.

In the German capital eleven-year-old Carla von Ulrich, born of German and English parents, struggles to understand the tensions all around her as her life and that of her family becomes engulfed by the Nazi tide. Her path through the tribulations ahead will include a deed of great courage and heartbreak. Into this turmoil step her mother’s formidable friend and former British MP, Ethel Leckwith, and Ethel’s student son, Lloyd. In the crucible of the Spanish Civil War Lloyd will eventually learn he must fight Communism just as hard as Fascism. But that’s in the future. For now he’s getting a firsthand look at the cruel reality of Nazism. He also encounters a group of Germans resolved to oppose Hitler—but are they willing to go so far as to betray their country? It’s a question of paramount interest to Volodya, a Russian with a bright future in Soviet intelligence.

At Cambridge Lloyd is irresistibly drawn to dazzling American socialite Daisy Peshkov. But she’s more interested in aristocratic Boy Fitzherbert—amateur pilot, party lover, and leading light of the British Union of Fascists. A driven social climber, Daisy believes love is something she can bestow upon whomever she likes, and that her main responsibility is to choose cleverly. She cares only for popularity and the fast set, until the war transforms her life, not just once but twice. In the United States, American brothers Woody and Chuck Dewar, each with a secret, are setting off on their own paths to momentous events, one in Washington, the other in the bloody jungles of the Pacific. And back in Berlin, Carla worships golden boy Werner from afar.

But nothing will work out the way they expect as their lives and the hopes of the world are smashed by the greatest and cruelest war in the history of the human race. The international clash of military power and personal beliefs that ensues will sweep over them all as it rages from the smoldering ruins of the Reichstag to the Battle of Cable Street in London’s East End to Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, from Spain to Stalingrad, and from Dresden to Hiroshima to the opening salvo of the Cold War.

These characters and many others find their lives inextricably entangled as their experiences illuminate the cataclysms that mark the century. From the drawing rooms of the rich to the blood and smoke of battle, from the corridors of power in Washington and Whitehall to the back alleys of postwar Berlin where the black market thrives, their lives intertwine, propelling the reader into dramas of ever-increasing complexity.

About the Author:

Ken Follett is widely regarded as one of the world’s most successful authors, with more than 130 million copies of his twenty-seven books in print. His last book, Fall of Giants, the first

novel in his Century Trilogy, was published in sixteen countries simultaneously and went straight to the number 1 position on bestseller lists in the United States, Spain, Italy, Germany, and France. Other novels, which regularly top bestseller lists around the globe, include Eye of the Needle, The Key to Rebecca, The Man from St. Petersburg, Lie Down with Lions, and the more recent New York Times bestsellers Code to Zero, Jackdaws, Hornet Flight, and Whiteout. In 1989 Follett surprised readers and critics alike by transforming himself from a writer of spy thrillers into a historical novelist with The Pillars of the Earth, and, eighteen years later, its sequel, World Without End, both of which were critically acclaimed international bestsellers. He lives in Hertfordshire, England, with his wife Barbara Follett, the former Labour Member of Parliament for Stevenage. Between them, they have five children and six grandchildren.

# # #

WINTER OF THE WORLD

by Ken Follett

Dutton

Publication Date: September 18, 2012

Price: $36.00

ISBN: 978-0-525-95292-3

Foreign rights sold to date

Bulgaria: Studio Art Line

Brazil: Sextante

Croatia: Algoriam

Czech Rep: Euromedia

Denmark: Cicero

Holland: Unieboek

Finland: WSOY

France: Laffont

Germany: Bastei Luebbe

Greece: Harlenic

Israel: Modan

Hungary: Gabo

Indonesia: Penerbit Erlangga

Italy: Mondadori

Japan: Softbank

Korea: Munhakdongne

Macedonia: Matica

Norway: CappelenDamm

Poland: Albatros

Portugal: Presenca

Russia: AST

Serbia: Evro-Giunti

Slovakia: Tartan

Slovenia: Mladinska Zalozba

Spain: RH Mondadori

Sweden: Albert Bonniers

UK: Macmillan

Twitter: @KMFollett

Facebook: www.facebook.com/KenFollettAuthor

YouTube: www.youtube.com/KenFollettAuthor

Available as a Penguin Audio, in unabridged and abridged versions

About

Ken Follett

Ken Follett is one of the world’s best-loved novelists. He has sold more than 100 million copies of his books. His last novel, Fall of Giants, was a number 1 bestseller in the United States, Germany, Italy, Spain, France, and many other countries.

He first hit the charts in 1978 with Eye of the Needle, a taut and original thriller with a memorable woman character in the central role. The book won the Edgar Award and became an outstanding film starring Kate Nelligan and Donald Sutherland.

Ken went on to write four more bestselling thrillers: Triple, The Key to Rebecca, The Man from St Petersburg, and Lie Down with Lions. Cliff Robertson and David Soul starred in the miniseries of The Key to Rebecca. In 1994 Timothy Dalton, Omar Sharif, and Marg Helgenberger starred in the miniseries of Lie Down with Lions.

He also wrote On Wings of Eagles, the true story of how two employees of Ross Perot were rescued from Iran during the revolution of 1979. This book was made into a miniseries with Richard Crenna as Ross Perot and Burt Lancaster as Colonel “Bull” Simons.

Ken then surprised readers by radically changing course with The Pillars of the Earth, a novel about building a cathedral in the Middle Ages. Published in September 1989 to rave reviews, it was on the New York Times bestseller list for eighteen weeks. It also reached the number 1 position on lists in Canada, Great Britain, and Italy, and was on the German bestseller list for six years. When The Times of London asked its readers to vote for the sixty greatest novels of the last sixty years, The Pillars of the Earth was placed at number 2, after To Kill a Mockingbird. (The sequel, World Without End, was number 23 on the same list.) Pillars was voted by 250,000 viewers of the German television station ZDF in 2004 as the third greatest book ever written, beaten only by The Lord of the Rings and the Bible. In November 2007 Pillars became most-popular-ever choice of the Oprah Winfrey Book Club, returning to number 1 on the New York Times bestseller list. The miniseries, produced by Ridley Scott and starring Ian McShane and Matthew Macfadyen, was broadcast in 2010. Ken appeared as an Anglo-French merchant.

After Pillars, Ken abandoned the straightforward spy genre for a while, but his stories still had powerful narrative drive, strong women characters, and elements of suspense and intrigue. Night Over Water, A Dangerous Fortune, and A Place Called Freedom followed.

Then he returned to the thriller. The Third Twin was a scorching suspense novel about a young woman scientist who stumbles upon a secret experiment in genetic engineering. Miniseries rights were sold to CBS for $1,400,000, a record price for four hours of television. The series, starring Kelly McGillis and Larry Hagman, was broadcast in the United States in November 1997. (Ken appeared briefly as the butler.) In Publishing Trends’ annual survey of international fiction bestsellers for 1997, The Third Twin

was ranked number2 in the world, beaten only by John Grisham’s The Partner.

The Hammer of Eden, another nail-biting contemporary suspense story, came in 1998. Code to Zero (2000), about brainwashing and rocket science in the fifties, went to number 1 on bestseller lists in the United States, Germany, and Italy, and film rights were snapped up by Douglas Wick, producer of Gladiator, in a seven-figure deal. Jackdaws (2001), a World War II spy story in the tradition of Eye of the Needle, won the Corine Prize for 2003. Film rights were sold to Dino De Laurentiis. Hornet Flight, about two young people who escape from German-occupied Denmark in a Hornet Moth biplane, is loosely based on a true story. It was published in December 2002. Whiteout, a contemporary thriller about the theft of a dangerous virus from a laboratory, was published in 2004, and made into a miniseries in 2009.

World Without End, the long-awaited sequel to The Pillars of the Earth, was published in October 2007. It is set in Kingsbridge, the fictional location of the cathedral in Pillars, and features the descendants of the original characters at the time of the Black Death. It was a number1 bestseller in Italy, the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Spain, where it was the fastest-selling book ever published in the Spanish language, outstripping the last Harry Potter book. The television miniseries was shot in Hungary in 2011 and stars Cynthia Nixon, Miranda Richardson, Ben Chaplin, and Peter Firth. Directed by Michael Caton-Jones, it is due to be screened around the world in autumn 2012.

A board game based on The Pillars of the Earth was released worldwide in 2007–2008 and won the following prizes: Deutscher Spielepreis 2007; Game of the Year 2007 in the United States (Games 100); Jeu d’annee 2007 (Canada); Juego del Año 2007 (Spain); Japan Boardgame Prize 2007; Arets Spill 2007 (Norway); Spiele Hit 2007 (Austria). It was a nominee in Finland, France, and the Netherlands and got a recommendation in Germany by the Jury “Spiel des Jahres.”

In 2008 Ken was awarded the Olaguibel Prize by the Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos Vasco-Navarro for contributing to the promotion and awareness of architecture. A statue of him by the distinguished Spanish sculptor Casto Solano was unveiled in January 2008 outside the cathedral of Santa Maria in the Basque capital of Vitoria-Gasteiz in northern Spain.

His current project is his most ambitious yet. The Century Trilogy will tell the entire history of the twentieth century, seen through the eyes of five linked families: one American, one English, one German, one Russian, and one Welsh. The first book, Fall of Giants, focusing on the First World War and the Russian Revolution, was published worldwide simultaneously on September 28, 2010. It won the Que Leer Prize in Spain and the Libri Golden Book Award in Hungary.

The second book is Winter of the World, about the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, and the development of nuclear weapons. It will be published in September 2012.

Family is very important to Ken, and he spends a lot of time with his children, stepchildren, and grandchildren. He was eighteen when he married his first wife, Mary. They were together for seventeen years and they are still close friends. They have two children. His second wife, Barbara, who now runs her husband’s business, was the Member of Parliament for Stevenage from 1997 to 2010. She held several ministerial positions during that time, including that of Under Secretary of State for Culture. Ken and Barbara divide their time between a rambling old rectory near Stevenage; an eighteenth-century town house in London and a beach house in Antigua. Through Barbara, Ken has three stepchildren and, altogether, they have six grandchildren.

Ken is a lover of Shakespeare and is often to be seen at productions of the Bard’s plays in London and Stratford. An enthusiastic amateur musician, he plays bass guitar in a band called Damn Right I Got the Blues, fronted by Floella Benjamin, and appears occasionally with the folk-rock group Clog Iron.

He was chair of the National Year of Reading 1998–99, a British government initiative to raise literacy levels. He was president of the charity Dyslexia Action for ten years. He is a fellow of the Welsh Academy and of the Royal Society of Arts. In 2007 he was awarded an honorary Doctorate in Literature (D.Litt.) by the University of Glamorgan, and similar degrees by Saginaw Valley State University, Michigan, where his papers are kept in the Ken Follett Archive; and (in 2008) by the University of Exeter. He is active in numerous Stevenage charities and was a governor of Roebuck Primary School for ten years, serving as chair of governors for four of those years.

Ken was born on June 5, 1949 in Cardiff, Wales, the son of a tax inspector. He was educated at state schools and graduated from University College, London, with an honors degree in philosophy. He was made a fellow of the college in 1995.

He became a reporter, first with his hometown newspaper the South Wales Echo and later with the London Evening News. While working on the Evening News he wrote his first novel, which was published but did not become a bestseller. He then went to work for a small London publishing house, Everest Books, eventually becoming deputy managing director. He continued to write novels in his spare time. Eye of the Needle was his eleventh book, and his first success.

A Conversation with

Ken Follett

1. Where did the idea for The Century Trilogy come from?

I was absolutely thrilled by the reaction of readers to World Without End and was looking to write something they’d like just as much. I wanted to recapture the magic of that book but, fond as I am of the Middle Ages, didn’t want to become a “medieval writer.” At some point, in trying to figure out how to do that, I thought of the twentieth century—the most dramatic and bloodthirsty century in the history of the human race; an ongoing drama of war against oppressive regimes and of people struggling for independence. It’s a thrilling story and it’s our story, one that has touched us all either directly or through our parents or grandparents.

2. Why did you choose to call this second of the three books Winter of the World?

The triumph of Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union and Hitler’s regime in Central Europe was a bloody tragedy for the human race. The keynote of that whole period was the struggle against the worst tyranny the world had ever known. The title Winter of the World perfectly captured the notion that my characters are desperately trying to survive a bigger kind of winter—one whose storms include Stalin’s purges and Hitler’s holocaust.

3. The trilogy follows the destinies of five interrelated families—American, Russian, German, English and Welsh. In Fall of Giants you took them through World War I and the Russian Revolution. This one takes them through the Great Depression and World War II. The third book will be about the postwar era and the Cold War. What made you choose these families in these countries as opposed to say a family in Italy or France?

It was kind of a technical thing. I tried to figure out the big turning points in history. For example, the decisions that led to the outbreak of World War I, or on how to respond (or not respond) to Hitler in the 1930s as he rose to power. After that I had to figure out how to describe people living through those turning points without having a hundred characters, a hundred points of view. When we read a novel we want to follow the destinies of a small number of people, yet there was a terrific range of real-life events to cover: the burning of the Reichstag, the Battle of Cable Street in London, speeches in the House of Commons or specific meetings in the White House, the Spanish Civil War, and so on. It required a certain exercise of ingenuity to minimize the number of characters to a level where readers would identify with them and want to follow

their stories, and yet have them credibly participate in numerous world-changing events, at a wide range of locations, during several key historical moments. That same calculus also drove the choices of which nations they were to come from.

Volodya Peshkov is a great example. As a Russian whose father is a Bolshevik general and senior diplomat, it was plausible to have him in Berlin in 1930, Spain in ’37, Berlin again in the early 1940s, and Moscow anytime I needed him there. I could even place him in Santa Fe in 1945, prying atomic secrets out of nuclear scientists.

4. Did you plot out the whole trilogy in advance?

When I started this I spent the first six months blocking out the whole trilogy. Eventually I realized outlining all three books in detail would take years and I didn’t want to make my readers wait that long. I satisfied myself with an approximate outline and then began focusing on book one. It has worked out rather well. I find it kind of funny that at the end of Winter of the World I was in a similar situation to where I was at the end of Fall of Giants—with all my key families experiencing a rash of pregnancies. Thank God they’re so fertile. It gives me the flexibility to plot out the next story.

5. What sort of research did you do for this book and the others in the trilogy?

There are, of course, literally thousands of books written about this period, especially about the Second World War. As I was doing my reading I knew there were key themes that were absolutely essential. My approach was to try to tell the stories of that time, and explore those themes, in ways that hadn’t been done before. That’s why my big scene about the Holocaust is not about Jews being killed but about the extermination of the mentally handicapped—adults and children. It’s an aspect of that wider story that hasn’t really been dealt with. Thankfully I was able to get hold of all the materials that exist on the subject. I’ve no doubt it will surprise, shock, and horrify a lot of readers. That’s the pattern my research followed: finding things to focus on, events that are intriguing and dramatic and not cliché, and then going into them in great depth.

6. Did you visit the locations of the key events in the book?

I’ve visited virtually all the places in which major scenes occur. Many of them—particularly in London, Washington, and Berlin—were already familiar to me. I was also familiar with almost all the places in France. (I didn’t actually walk across the Pyrenees into Spain but thankfully there are several recollections and memoirs by people who made the trip.) One place I visited that was particularly interesting was the Spanish town of Belchite, the site of a key battle of the Spanish Civil War featured in the book.

7. What was Belchite like?

It was quite fascinating and moving. Although a new town has been built nearby, the old town of Belchite was pretty much left as it was at the end of the battle featured in the book—a “live” monument of war. Some of the buildings, including the church of San Agustin, are still standing; others are half-demolished. Having written the battle scene at the church based on memoirs and

history books, it was wonderful to actually go there and check out the extent to which my imagination matched the real thing. In fact it was quite spooky walking the streets on which my soldiers fought, and being in the church where my pro-Franco rebels defended their positions. In one scene I imagined several characters assaulting the church, knocking holes in the walls of adjacent houses on an approaching street so they could advance without exposing themselves to what surely would have been withering defensive fire. It was a unique experience to actually go there and see holes in the walls leading from house to house.

I also explored the streets of London I describe in writing about the Battle of Cable Street—an infamous attempt by British Fascists, under the protection of the Metropolitan Police, to march against the Jewish community in London’s East End. I walked all the streets my character Lloyd Williams walked that day when anti-Fascists erected barricades and clashed with police trying to clear the road so the march could take place. Unlike Belchite, Londoners continued to develop and rebuild the area so it doesn’t look much like it did in 1936. However, the big sideway junction I describe is still there. It’s still the gateway to that part of the city.

8. Are any of your fictional characters based on real people?

The character Ethel Leckwith is loosely based on Ellen Wilkinson, a labor MP in 1924 and minister of education in Clement Attlee’s government after the war. She was known as “Red Ellen.” (Some said it was because of her red hair, others because she was a left-winger.) The Berlin spy network I describe is very closely based on a real spy ring called “Red Orchestra,” which consisted of Germans who opposed Hitler and reported to Moscow. One of them, a wealthy Berlin playboy, served as the inspiration for my character Werner Franck. All the scenes in which the Gestapo tried to track down members of the network as they radioed back to their handlers in Russia actually happened. Similarly, the description of the execution chamber and Lili’s beheading are based on real events.

9. Looking back, what’s your take on the political situation of that era?

World War II was seen at the time as a great crusade against evil, and our perceptions of it haven’t really changed. Our enemies—the Japanese and German empires—were despicable regimes, military dictatorships. During the First World War it wasn’t out of the question to ask who really were the good guys and bad guys. In the Second World War those distinctions were very sharply drawn. So people’s perceptions at the time were pretty accurate. Of course we were all rather forgiving of the Soviet Union because they were our allies. That didn’t last very long once the war ended. Nevertheless there was a period when the Communists did extremely well in general elections throughout Europe because of what they had done during the war.

Serving as the heart of the resistance in many countries, the Communists had bravely pushed back against Hitler in Germany and against Fascism in Spain, France, and Italy, earning great support there and elsewhere. What was interesting was how quickly that support fell away. By the second round of postwar elections in the late 1940s it had plummeted. From then on there was never any serious hope for the Communists to win free democratic elections in Europe.

10. One of the central aspects of your story is the rise of Fascism in Germany. Much has been written about how that happened in one of the world’s most cultured and educated countries in the world. What’s your take?

There were two key factors. One was the economic slump that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929, during which Germany suffered more than any other country in the world. We get panicky today if unemployment reaches anywhere near 10 percent. That’s considered a major crisis. In 1933 unemployment in Germany was a staggering 40 percent. Imagine living in a country where almost half the men you see walking down the street are desperately trying to figure out how they’re going to feed their families. That sort of situation drives people to extremes.

The other key factor was that Germany didn’t have a lot of experience with democracy. By the time the Great Depression came along, the U.K. had had democracy for hundreds of years. In the U.S. the democratic tradition was equally strong. Germany had been democratic for only fifteen years or so. They didn’t have faith in democracy to solve their problems. These two factors were a deadly combination that spelled Germany’s doom. Once you have that kind of situation it’s easy to get people to believe in a philosophy of hate; easy to convince them all their problems are the result of some group of “aliens”—whether it’s German Jews or African Americans, Polish immigrants or Mexicans from across the border. Next thing you know you’ve got all these guys in bars and taverns and beer halls, banging on the table saying, “It’s their fault, we ought to get rid of them.” Unfortunately that works all too well in unhealthy democracies or places where people are desperate.

11. There’s certainly a lot of anti-immigrant, ultraconservative, some would even say nationalistic sentiment in a great many countries today. Do you think there could ever be a rise in Fascism again?

Do I think it will happen in the United States? No. But whenever you ask the opinions of people who have lost their rights, they always say they should have fought against it right at the start. That’s why, even in places where we feel comfortable with our democracy, or where we believe ultra-right-wing movements will never gain traction, we need to say “hell no” when we find ourselves using a so-called “national emergency” as an excuse for compromising civil liberties.

12. In USA Today’s review of Fall of Giants, it was said that you had outdone yourself and that readers would be sucked in, consumed for days or weeks, and come out the other side both entertained and educated. Do you still read the reviews of your work? And after so many years of success does that kind of review still excite you the way it might have earlier in your career?

I do read my reviews. And that kind of thing is very important to me. I particularly love it when readers—whether a reviewer in a national newspaper or someone I meet on the street—says once they started reading they couldn’t stop. It makes me feel like I must have done a pretty good job. On a Concord flight from London I once found myself seated next to John McEnroe. It was the day after he had won one of his singles titles at Wimbledon. I told him, “You’re probably bored with hearing this, but congratulations.” He said, “Oh no, I’m not bored with it at all.” That’s exactly how I feel when people compliment my work.

13. Plenty of historians have written about this era. Who among them do you particularly like or respect?

Richard Overy, who has written extensively about World War II and the Third Reich, is one of the best living historians and a great writer. He’s very easy to read. And there’s a new history of the Second World War by Max Hastings titled All Hell Let Loose, which was published late last year. Politically he and I are on opposite ends of the spectrum, but his book is absolutely brilliant. After writing Winter of the World I have a deep sense of the challenges he faced. He did with nonfiction what I’ve tried to do here—tell the fascinating story of WWII in one volume.

14. Winter of the World has a number of real historical characters, including several heads of state. What are you thoughts on the key leaders of that era?

In my opinion FDR was one of the greatest presidents of all time. He brought the United States out of its massive economic slump and was a first-rate wartime commander. People forget at the beginning of the war in the Pacific nobody was sure America would win. Roosevelt galvanized the country and turned that around. Most pundits thought his successor, Harry Truman, who pushed through the founding of the U.N., would be a terrible president but he was much better than anyone expected.

As you can tell from the book I think Ernest Bevin was a fascinating and admirable character. Orphaned at age eight and with little formal education he overcame a horrible background to become one of the greatest foreign secretaries England has ever known. It was Bevin who talked George Marshall into establishing the Marshall Plan, which basically saved postwar Europe. Clement Attlee was also a great man. After Winston Churchill won the war everyone assumed he’d be a shoe-in to become prime minister. To everyone’s surprise Attlee beat Churchill in the election. He then proceeded to transform Great Britain, turning it into the country it is today. We don’t have the same agonizing over healthcare that Americans do because Attlee fixed the healthcare system in 1947. One of the reasons I find him so intriguing is that he didn’t have Churchill’s obvious leadership qualities: Churchill was a wonderful cheerleader, a brilliant orator with an ability to make people feel better under terrible circumstances. Attlee wasn’t capable of any of that. He wasn’t that good a speaker. But he was a hell of a prime minister.

15. What about Stalin and Hitler?

The more I studied Stalin and Hitler the more I realized they were kind of stupid as well as being ruthless. They both made terrible decisions. For example, Roosevelt may have wanted to bring the United States into the war in Europe, but his problem was that it would have been unpopular with a vast majority of Americans. Hitler took care of that when he declared war on the United States in December 1941. It was an incredibly stupid move on his part. As for Stalin, he ignored a vast amount of intelligence indicating Germany was going to invade the Soviet Union in 1941, insisted on telling the world there’d be no invasion, and refused to let the Red Army prepare. In any system other than an absolute tyranny that decision would have destroyed the leader. One of the many reasons tyrannies are a bad idea is when tyrants make dumb decisions no one dares tell them they’re wrong.

16. Some writers live in dread of their books being turned into films or miniseries. How have you enjoyed the experience?

Seeing good actors giving good performances bringing to life characters I’ve invented and speaking some of the lines I’ve written is a huge thrill. When it all goes well it’s great. When it goes badly you sort of cringe when you see what’s on the screen. But you have to take that risk. I’m pleased and proud that some of my stories have made good film and TV. It confirms the strength of the story that it can be transformed from one medium to another. So despite the occasional catastrophe I’m basically pleased with what’s been done.

17. In describing book one of The Century Trilogy, you’ve said you want readers first of all to enjoy the story, but second to feel, when they put the book down, that they understand things that used to seem incomprehensible. In the case of Fall of Giants you were referring to why World War I happened and why the Bolsheviks won the Russian Revolution. What is it you’re trying to impart in Winter of the World?

I think people are very vague about how Hitler actually managed to take control of Germany the way he did. That’s why I opened Winter of the World with that short period of a few days when he came to absolute power. Many people have asked the question you asked earlier: How could this have happened in a civilized country? In that opening chapter I tried not just to show what it felt like to be there but also how things clicked into place for Hitler: how there were too few people brave enough to speak out against what was going on; too many who were afraid to speak out at all; and how all of that worked together to let him in. Hopefully, in writing that scene, I’ve explained how a tragedy like Hitler’s access to power happened.

18. Do you think someone like Hitler could be elected today?

It’s hard to imagine isn’t it? People know much more now than they used to. By that I mean there’s so much more information available. In some cases the effect is regrettable. In his day FDR was able to organize things so you never saw his wheelchair. I bet half the American people didn’t know he was disabled. And because of that the United States got a great president. If he were running for office today, I doubt he’d win the nomination let alone a general election. Pictures of him in his wheelchair would be everywhere. Nevertheless my belief in freedom of information makes it impossible to say we should go back to that era. Look at what happened to the character Carla when she discovered the disabled were being killed. She couldn’t go to the press because there was no free press. She couldn’t turn to the courts or the police because they too were under Nazi control and so was Germany’s parliament. She quickly realizes people had been protected because those institutions had been free, and with those freedoms abolished the Nazis could do anything or kill anyone they wanted. That’s an expression of my fundamental political philosophy. Even though the press sometimes abuses its freedom, an open and free press is perhaps one of the most important safeguards against someone like Hitler coming to power.

19. What do you want readers to get out of this book?

The miracle of literature is that you can read a story you know is made up but react to it as if it was real. That’s what gets us about literature. We become involved in the destinies of the

characters we’re reading about even though we know they’re fictitious. Tears come to our eyes; we tremble; we sit on the edge of our seats at a key moment. That’s what I want any time I write a story. I want readers to get emotionally involved so that when they put the book down they’ll want to call a best friend and say, “I’ve just finished a book that you’ve got to read!”

# # #

Historical Events Providing Key Scenes and Turning Points

in

WINTER OF THE WORLD

Book Two of The Century Trilogy

by

Ken Follett

The Burning of the Reichstag in Berlin (February 27, 1933)

Germany’s recently elected chancellor, Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, uses the fire to consolidate power. A day after the burning he persuades Germany’s aging president, Paul von Hindenburg, to approve the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspends civil liberties, including freedom of the press and the right to assemble, and allows the Nazis to arrest political opponents and shut down dissent.

Germany’s Parliamentary Elections (March 5, 1933)

Despite the crackdown on its opposition the Nazi Party makes only small gains in the elections. Still, with many Communist leaders in prison and other opposition politicians intimidated, the Nazis will soon pass the Enabling Act, which will strip the Reichstag of its legislative powers and give Hitler dictatorial power over Germany.

Boycott Jews Day (Sunday April 1, 1933)

The Nazis stage a boycott of Jewish shops and businesses. Yellow stars are daubed on the windows of Jewish-owned shops. Brownshirts stand at the doors of Jewish-owned department stores, intimidating people who want to go in. Jewish lawyers and doctors are picketed.

Battle of Cable Street (October 4, 1936)

The Blackshirted British Union of Fascists, led by Oswald Mosley, attempts to march into London’s East End and the overwhelmingly Jewish borough of Stepney. Despite the strong likelihood of violence and pleas by local political and civic leaders, the government refuses to prevent the march or even divert it. Instead they provide thousands of police—mounted and on foot—to prevent any disruptions by anti-Fascist counter-demonstrators. With cries of “They Shall Not Pass,” hundreds of thousands of East Enders flood into the area, erect barricades, and engage in a series of running battles with police trying to clear a path for Mosley and his Fascist followers who are ultimately forced to abandon the march.

Battle of Belchite (August 1937)

The well-defended but strategically worthless town of Belchite, in the Aragon region of northeastern Spain, is the site of some of the most desperate hand-to-hand fighting seen during the Spanish Civil War. Faced with withering fire in the streets from well-positioned antidemocratic rebel defenders, Spanish Republican forces attempting to take the town are forced to knock holes in the walls of adjacent houses and clear each one as they advance street by street.

High drama in Parliament as British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain responds to Germany’s attack on Poland (September 2, 1939)

In the wake of the invasion Chamberlain delivers an ambivalent speech indicating Britain will not immediately come to the aid of its ally or deliver any kind of ultimatum to Germany. As Labour Party deputy leader Arthur Greenwood rises to speak, Conservative MP Leo Amery, angered at the government’s vacillation and convinced the prime minister is out of touch with the sentiment of the English people, calls across the floor “Speak for England, Arthur.” The implication is clear: Chamberlain has failed to do so. The following day the prime minister announces the country is at war with Germany.

The “Norway Debate” (May 7 and 8, 1940)

This famous debate in the House of Commons, supposedly about the conduct of the war in Norway, brought to a head widespread dissatisfaction with Chamberlain’s government and its appeasement of Fascism that left the prime minister with little credibility as a war leader. One of the most dramatic moments of the debate came when Conservative MP Leo Amery, quoting Oliver Cromwell, told Chamberlain he must step down: “You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!” Although the government won a vote of confidence, it was with a greatly reduced majority. With support crumbling for the prime minister even within his own party he ultimately had no choice but to resign.

The Battle of France (May 1940)

Germany’s invasion of France, Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg began on May 10. By May 20, a week after emerging unexpectedly from the Ardennes forest, German forces had reached

the coast of the English Channel, cutting off the French Army and nearly all of the British Expeditionary Force that had advanced into Belgium.

The Battle of Britain (Summer 1940)

By the summer of 1940 the war in Continental Europe appeared to be over. Germany had won. Europe was Fascist from Poland to Sicily and from Hungary to Portugal. There was no fighting anywhere. Rumors said the British government had discussed peace terms. But Prime Minister Winston Churchill did not make peace with Hitler, and the German Luftwaffe’s air campaign against the United Kingdom began. At first civilians were not much affected. The Luftwaffe bombed harbors, hoping to cut British supply lines. Then they started on air bases, trying to destroy the Royal Air Force. By early fall their tactics switched once more and the focus shifted to areas of political significance and cities/civilian targets. (In some respects this shift was in response to the British government having approved the bombing of targets in German cities in May.)

The start of Operation Barbarossa and Stalin’s breakdown (June 1941)

Despite various warnings Germany’s invasion of the USSR took the Soviets completely by surprise. When the attack began many forward units of the Red Army had no live ammunition and planes had been lined up neatly on airstrips with no camouflage, allowing the Luftwaffe to destroy a vast number of Soviet aircraft in the first few hours of the war. Army units—thrown at the advancing Germans without adequate weapons, air cover, or intelligence about enemy positions—were annihilated. And standing orders forbidding retreat and insisting every unit fight to the last man turned every defeat into a massacre. By the first week of the operation German forces had pushed three hundred miles into Soviet territory. It was around this time that Stalin virtually disappeared from sight, famously telling his generals “Everything’s lost. I give up. Lenin founded our state and we’ve fucked it up” before fleeing to his country house outside Moscow. The Soviet leader remained incommunicado for three days until a small delegation of politburo members arrived and begged him to return to work.

Aktion T4 (August 1941)

Begun in 1939, Nazi Germany’s secret program to exterminate the mentally ill and the handicapped in order to cleanse the Aryan race of people considered genetically defective and a financial burden did not remain secret for long—particularly because the majority of those killed had families actively concerned about their welfare. (In some cases families could tell the causes of death notified were false such as when their loved one, who they were told died of appendicitis, had had their appendix removed years earlier.) By August of 1941 the program was attracting angry protests from a normally passive public—the sole example of an action by the Nazi regime to do so—and was canceled in order to avoid an open confrontation with churches of all denominations. T4 personnel were transferred to the east to begin work on a vastly greater extermination program: the final solution. Despite the program being officially shut down, the killing of the mentally handicapped continued albeit, in a less systematic manner.

The Atlantic Conference (August 1941)

It was at this historic meeting between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill at Placentia Bay, off the cost of Newfoundland, that Britain and the United States drafted the Atlantic Charter, which defined the Allied goals for the postwar world. Among the Charter’s

principal points were that both countries agreed not to seek territorial expansion, lowered trade barriers, established freedom of the seas, disarmed aggressor nations, and commited to supporting the restoration of self-governments for all countries that had been occupied during the war and allowing all peoples to choose their own form of government. The Charter is hailed as a trumpet blast for freedom, democracy, and world trade.

The Battle of Moscow (Fall and Winter of 1941)

As the capital of the USSR and the largest Soviet city, Moscow was one of the primary military and political objectives for Axis forces in their invasion of the Soviet Union, but by October, with rains turning the roads into mud baths, the German dash for Moscow slowed to a crawl. The frosts of November provided little relief. Although roads were hard enough to travel on at normal speeds, the worsening cold quickly disabled trucks, tanks, artillery, and aircraft of all types. On December 4, with temperatures hovering near -35° centigrade, Soviet forces moved out of the city to the north, west, and south and took up their positions in a last-ditch effort to turn back the slowly advancing Germans. Over the next several days they succeed in breaking through German lines in many places, which led to a rapid withdrawal by the ill-prepared and frostbitten Germans.

Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941)

The “date that will live in infamy.”

Station HYPO and the attack on Midway (May–June 1942)

Also known as Fleet Radio Unit Pacific, the U.S. Navy signals monitoring and cryptographic intelligence unit in Hawaii had been working day and night to crack JN-25b, the new code of the Imperial Japanese Navy. By May they had made enough progress to confirm Midway Island as the target of an impending Japanese attack, allowing Admiral Nimitz to set a trap for the Japanese. The Battle of Midway marked the beginning of a new kind of naval warfare and made it clear the Pacific war would be won by planes launched from ships.

The Manhattan Engineer District (September 1942)

This deliberately uninformative name camouflaged a team that was trying to invent a new kind of bomb using uranium as an explosive. With FDR unhappy that the project was moving too slowly, General Leslie Groves, chief of construction for the entire U.S. Army, was placed in charge in September 1942 and tasked with imposing order on the hundreds of civilian scientists and dozens of physics laboratories involved in the Manhattan Project.

The first nuclear chain reaction (December 2, 1942)

Built in an unheated squash court under the west stand of a disused stadium on the University of Chicago campus, Chicago Pile-1 was the world’s first man-made nuclear reactor. A cube of gray bricks reaching the ceiling of the court, the pile cost a million dollars and could blow up an entire city. It was there that the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated. Afterward Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard turned to his colleague Enrico Fermi, who constructed the pile, and said, “My friend, I think this will go down as a black day in the history of mankind.”

The Moscow Conference (October 1943)

This third conference between the major allies of the war was a series of meetings between the foreign ministers of the United Kingdom, United States, and the Soviet Union—Anthony Eden, Cordell Hull, and Vyacheslav Molotov. As a result of this conference the representatives released the Joint 4-Power Declaration to establish a United Nations to maintain peace in the postwar world. Agreements were also reached on a European commission on German surrender terms, plans for restoring the sovereignty of Austria, and matters regarding the recent surrender of Italy.

The Bougainville Campaign (November 1943)

The 125-mile long island, occupied by the Japanese since 1942, was the site of two Japanese naval air bases. On November 1, U.S. marines launched the first phase of Allied operations to retake the island. Their initial objective was to establish a beachhead along the lightly defended west cost and win enough territory to build an airstrip from which to launch attacks on the Japanese bases.

D-Day (June 6, 1944)

“The Longest Day”

The Battle of Berlin (Spring 1945)

With just 110,000 Germans defending the capital of the Third Reich against a million Soviets, this final major offensive of the European Theater of World War II lasted for roughly two weeks. Long whipped into an anti-German frenzy by the Kremlin and a massive campaign of hate propaganda, Soviet troops during the battle, and in the days immediately afterward, engaged in mass rape, pillage, and murder of German civilians. Prisoners were killed, homes were looted and wrecked, women were raped and on some occasions nailed to barn doors.

The San Francisco Conference (May–June 1945)

Representatives of fifty countries meet in San Francisco to draw up the United Nations Charter. Things began badly for the United States. At a pre-conference meeting at the White House, President Truman had clumsily offended Soviet foreign minister Molotov. As a result Molotov arrived in San Francisco in a foul mood, announcing he was going home unless the conference agreed immediately to admit Belorussia, Ukraine, and Poland. At one point during the deliberation U.S. Secretary of State Stettinius and British foreign secretary Anthony Eden sparred with Soviet foreign minister Molotov over admitting Poland unless Stalin permitted elections there. The Belgians proposed a face-saving compromise—a motion expressing the hope that the new Polish government might be organized in time to be represented in San Francisco—a Soviet walkout was avoided and the U.N. Charter was signed on June 26.

Trinity (July 16, 1945)

In southern New Mexico, not far from El Paso, in a desert called Jornada del Meurto (the Voyage of the Dead), the men of the Manhattan Project tested the most dreadful weapon the human race had ever devised. When asked why the test was code-named Trinity, J. Robert Oppenheimer would cite a poem by John Donne: “Batter my heart, three person’d God.”

The General Election of 1945 (July 1945)

Fifteen days after VE Day, Winston Churchill called a general election. Most people assumed Churchill would wait until the Japanese surrendered. Labour leader Clement Attlee had suggested an election in October. Churchill wrong-footed them all. Virtually every pundit assumed the wartime leader and his Conservative party would win. Every pundit was wrong. When all the results were in, Attlee’s Labour Party had won a surprise landslide over Churchill’s Conservatives.

Moscow Conference (March–April 1947)

It was at this fourth meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers that the future of Germany, and therefore of Europe, was supposed to be decided. During the conference Soviet foreign minister Molotov demanded that Germany pay ten billion dollars to the USSR in war reparations. The Americans and British protested this would be a deathblow to Germany’s sickly economy (which was probably what Stalin wanted). The following day, when U.S Secretary of State Marshall proposed that the four allies abolish the separate sectors of Germany and unify the country, Molotov refused to discuss the matter until the question of reparations had been settled. After six weeks with no forward movement the conference ended.

The Announcement of the Marshall Plan (June 1947)

Believing that a solution for postwar Germany could no longer wait, Secretary of State George Marshall, in a speech to the graduating class of Harvard University, announces America’s intention of offering aid to promote European recovery and reconstruction. The speech contained few specifics and instead called on the Europeans to draft a plan. British foreign secretary Ernie Bevin quickly organizes a conference in Paris that gives a resounding collective European welcome to the Harvard speech.

The Czech coup and the death of Jan Masaryk (February–March 1948)

Bevin’s goal of bringing Germany into the Marshall Plan while keeping the USSR out was furthered when Stalin commanded countries of East Europe to repudiate Marshall Aid. The Czech Communist Party’s takeover of the government there in February was another great boon to Bevin’s plans. Believing American taxpayers didn’t want to foot the bill, the U.S. Senate could possibly have rejected the plan. The coup in Czechoslovakia helped persuade them otherwise. Just two weeks after the coup Czech foreign minister Masaryk was found dead, dressed in his pajamas, in the courtyard of the foreign ministry. Although his death would be ruled a suicide, many believe he was murdered by the new Communist government.

Crisis in Berlin (June 1948)

In a move conducted without the cooperation of the Soviets, the Americans announce during an evening radio broadcast on Friday, June 18, that Germany will have a new currency—the deutschmark—as of Monday morning. The following morning the Soviets announce it will be a crime to import deutschmarks into East Germany, including Berlin, which they consider part of their zone. The Americans immediately denounce the phrase and reaffirm Berlin to be an international city. When the Communists fail to bully the Berlin city council into accepting a Soviet decree to reform East Germany’s currency and make the new “ostmark” the only legal tender in all sectors of the city, the Soviets announce the Berlin Blockade. The initial stages of the Berlin Airlift will begin less than a week later.