Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, #FashionandVirtue 1520–1620 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art Our Coverage Sponsored by Maine Woolens

Ensemble. Early 20th century. Russian. Length (a): 20 in. (50.8 cm) Length (b): 32 in. (81.3 cm) Length (c): 28 in. (71.1 cm) Length (d): 131 in. (332.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Administration Fund, 1924

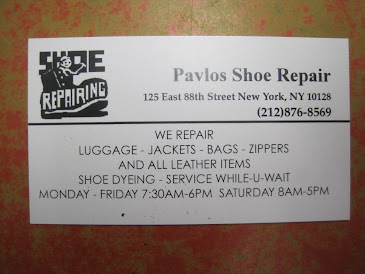

Maine Woolens is a weaver of blanket and throws located in Brunswick, Maine. We work primarily with natural fibers, like cottons and worsted wools and are committed to using renewable natural fibers from American growers whenever possible. We do piece dyeing and package dyeing in house and the combined experience of our excellent employees exceeds 300 years. Our wool and cotton blankets and throws are 100 percent machine washable, soft and luxurious to the touch, cozy warm and comfortably light. We have many styles to choose from. Our clients are very positive about our products and happy to support a Made in Maine, USA company. Jo Miller is a Mover and Shaker:

Visit our website at www.mainewoolens.com

We have been highly recommended by Whom You Know:

Maine Woolens, affordable luxury and tradition.

***

October 20, 2015–January 10, 2016

Exhibition Location: Robert Lehman Wing, Galleries 964–965, Lower Level

Printed sources related to the design of textile patterns first appeared during the Renaissance when six intricate, interlaced “knotwork” designs, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and later copied by Albrecht Dürer, marked the beginning of a fruitful international exchange of pattern designs. Starting in the 1520s, small booklets with textile patterns were published regularly, and these pocket-size, easy-to-use publications became an instant success, essentially forming the first fashion publications. These books were not made for the library but for the active use of their 16th-century owners across all levels of society, who were interested and invested in textile decoration as a means of self-expression and transformation of their households and dress. Users of the books tore out the pages and pasted or nailed them to workroom walls for inspiration. Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620, an exhibition drawn largely from the Metropolitan Museum’s own collections, will combine printed pattern books, drawings, textile samples, costumes, paintings, and various other works of art to evoke the colorful world in which the Renaissance textile pattern books first emerged and functioned.

The exhibition is made possible by the Placido Arango Fund and the William Randolph Hearst Foundation.

The Metropolitan Museum’s Department of Drawings and Prints boasts one of the world’s most important collections of early textile pattern books. The last time these books were featured in an exhibition at the Museum was in 1938, when the collection had been established. Recent conservation work on these books, facilitated by a grant from the Museum by the Library Division of the New York State Education Department, has provided the opportunity for a new exhibition to highlight this remarkable collection and focus on the interesting stories the books tell about textile pattern design and the want for models; enterprises in early book publishing; and artistic exchange throughout Europe.

During the first quarter of the 16th century, the market for publications of textile patterns quickly expanded and the exchange of designs and ideas was established between Italy and the countries north of the Alps. The small booklets, each containing a few dozen pattern designs, were published on a regular basis, their publishers proudly advertising the novelty of the patterns they had collected from all over Europe. The books became highly influential sources that both instructed and inspired many in the arts of making embroideries, weavings, and lace, as can be seen in surviving costumes and textiles of the period. Although pattern books are now often perceived as mere auxiliary tools for those not clever enough to come up with their own designs, the illustrated title pages, introductions, and publishers’ notes in these prints and booklets suggest a function and appreciation that was far more complex. The wide reach of these publications meant they were easily adapted for educational purposes, instructing women and young textile makers in the art while simultaneously dispensing advice on proper conduct and a virtuous lifestyle.

The Metropolitan Museum’s encyclopedic collection allows for meaningful, multifaceted presentations that support and enhance these stories and illustrate the popularity of the pattern books and their ubiquitous use throughout Europe. Fashion and Virtue will feature, for example, contemporary embroidery samples from the collection of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts and portraits from the collection of European Paintings that will show the many ways in which embroidery and lace were used in contemporary costume. Objects from the Metropolitan’s Costume Institute, the Robert Lehman Collection, and the departments of Islamic and medieval art will be also be on view with select loans from the Victoria and Albert Museum, Museum Bautzen (Germany), the Rhode Island School of Design, and the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Fashion and Virtue is organized by Femke Speelberg, Associate Curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin entitledFashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520-1620 written by Femke Speelberg. It will be on sale in the Museum’s book shop in early November.

The Metropolitan’s quarterly Bulletin program is supported in part by the Lila Acheson Wallace Fund for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, established by the cofounder of Reader’s Digest.

On November 6, designer Todd Oldham will join Femke Speelberg for a conversation about the exhibition.The exhibition will be featured on the museum’s website, as well as on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter via the hashtag #FashionandVirtue.