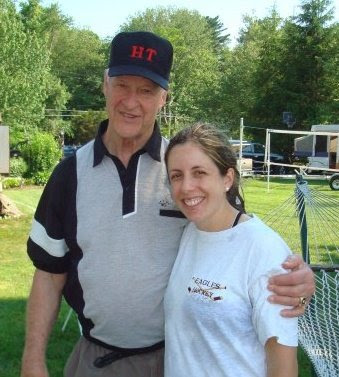

#SmallScreenScenes #Britbox @BritBox_US #BBC #America Gideon's Daughter Starring #BillNighy and #EmilyBlunt Highly Recommended by #WhomYouKnow @ManhattanPeachy #PeachyDeegan

We have been absolutely wild about all the fabulous offerings on BritBox ever since we got it, and the depth of quality on this platform is unbelievably excellent. It is high time for summer hibernating in Manhattan and if it is too hot for you to eat, sleep, work or nearly anything else, what you can do is sit still and cool off with BritBox.

It is fun to search for what you don't know and we've made a career out of that.

In this particular circumstance, we wanted to see what kind of movies BritBox has because we know they are known for their tv shows and we wanted to see if they are a one-trick pony.

They are absolutely not a one-trick pony.

Bill Nighy and Emily Blunt are obviously completely marquee names evidenced by their quality of acting, and teamed up together here as father and daughter, they deliver a performance that supersedes noteworthy. A tight, intelligent drama awaits you in Gideon's Daughter and the realization of what is important will wow you.

How would producer Nicolas Brown describe Gideon's Daughter, Stephen Poliakoff's deeply affecting story about two desperately lost souls who find a most unlikely connection against the remarkable backdrop of the rise to power of New Labour, the death of Princess Diana and the birth of the Millennium Dome?

"One of Stephen's favourite words to describe his work is 'vivid' and I think that pretty much sums up this film," declares Brown, who also produced Poliakoff's other, inter-linked drama, Friends and Crocodiles, as well as Nicholas Nickleby, White Teeth, Deceit, Hope and Glory, and Charles Dance's acclaimed directorial debut, Ladies in Lavender. "I couldn't have put it better myself."

The drama zooms in on two characters in extremis. Gideon (played with haunting sadness by Bill Nighy) is a hotshot publicist and the widowed father of a sullen teenage daughter (Emily Blunt).

He has been driven to the edge of a nervous breakdown by her emotional detachment from him: she is still resentful that he has been a serial adulterer and that he was out of the room calling his mistress as her mother lay dying of cancer in hospital.

She also feels that his love for her is suffocating - he's just coming on too strong. To underline their distance, she is about to fly the nest and take up a place at university in Edinburgh.

However, Gideon is hiding his pain and to the outside world nothing seems wrong with him. In fact, quite the contrary: New Labour politicians and influential media players are queuing up to court him.

Even though he is thoroughly disillusioned with the manipulative world of spin and focus group, Gideon is viewed as nothing short of a PR genius.

He can only really express his agony to a fellow soul in torment. Stella (portrayed with aching poignancy by Miranda Richardson) is mourning the death of her young son, killed while out riding his bike for the first time. Afraid of sleep, she is attempting to lose herself and shut out her sense of bereavement by working in an all-night supermarket where she keeps guinea pigs in the back.

Gideon does not meet Stella in auspicious circumstances. They bump in to one another when Stella's ex-husband tries to accost one of Gideon's clients, a New Labour minister, about the Government's lack of response to their son's death.

But after this unhappy start, Gideon and Stella soon find a real bond, brought together by a shared sense of grief and loss.

Without ever overtly waving placards during the course of the drama, the writer-director succeeds in talking about the way society has evolved over the past eight years. Poliakoff conveys the social developments of the last decade through the prism of these compelling characters.

The specific reflects the universal. So the particular story of Gideon has a wider resonance and says something about the way we have been governed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

"The film is trying to open a door onto the world and make people see the very recent past in a different light," Poliakoff observes. "By telling a very visceral, personal love story, it aims to throw light on how we as intelligent adults feel about the world."

He goes on to muse that: "In the summer of 1997, the seeds were sown for today's worship of celebrities and the way in which the Government manages surfaces. Gideon is this PR guru, and everyone believes that he can solve their problems. He is a mixture of a psychiatrist and a priest.

"He stops listening, but the irony is, the less he listens, the more people want him and take what he says as Gospel. Presentation has become so much more important than ideas. We've now had eight years of a New Labour Government, and no one can point to a Big Idea. All they can point to is a massive amount of presentation."

The story is told from Gideon's point of view. "Instead of portraying a thick-skinned PR person controlling everything, I wanted to reverse it," Poliakoff says.

"So we're inside Gideon's mind and we hear him saying to himself, 'Hang on, why is everyone taking me so seriously?'

"People have lost faith in their political leaders, and they are constantly searching for different solutions in everything, from right-wing religion to alternative thinking. Gideon is gripped by a sense of spiritual emptiness that is only redeemed through his relationship with Stella. That removes him from the shallowness of his professional life."

The writer-director took the Millennium Night celebrations as his starting point for his exploration of society's fixation with spin.

"Why was Millennium Night such an unmitigated disaster when so many clever people had been working on it for so long? It was the same with the Millennium Dome. It was meant to be about the future, but it served up such a sterile vision.

"Gideon says to the Government, 'You'll do more business in a pencil museum in the Lake District than in the Dome if you just fill it with lists,' and he is proved right.

"The Dome failed completely and utterly because it showed a staggering lack of imagination. It was incredibly arrogant of politicians to think they were in showbiz. They were so out of touch; it was a moment of extraordinary hubris. It paints a telling portrait of how this Government has gone so awry."

Of course, Poliakoff's artistry ensures that the impact of Gideon's Daughter is not limited to recounting the history of New Labour spin. Like any great work of art, it also has universal significance.

According to the writer-director:"The story is about Gideon's voyage, but underneath that it is also about more universal themes. Everyone is either a son or a daughter or a parent, and the film reflects every parent's fears for their children.

The world is becoming a more and more dangerous place.

"It is also about knowing one's children. Gideon is already distant from his daughter when he has the typical middle-aged male executive moment of not being faithful to his wife. His daughter won't forgive him, and he becomes even more alienated from her. It's about coming to terms with how our children judge us.

"Also, with the advance of technology and many children now having TVs and computers in their rooms, there is far less family time with the whole clan seated round the table. There has always been an element of mystery for parents about their children, but that has now become a huge part of Western civilisation. Does one ever really know what's going on in one's children's heads?"

In addition, Gideon's Daughter very movingly addresses the theme of bereavement. The character of Stella shows what can become of parents when the unthinkable happens and they lose a child.

"Moving on and thinking positively have become the great clichés after a bereavement," Poliakoff reckons. "When Stella erupts with grief at one point in the film, she cries, 'You can see in people's eyes that they're thinking, 'Surely it's time to move on, surely it's getting less'. Sorry, but it isn't getting the slightest bit less.'

"Everything is over so quickly these days. We move on, we move on, we move on because communication is so quick and people are hungry for the next thing. That is reflected in the Government's obsession with presentation. People in power think nothing hangs around for very long. They have bought into the idea that there's an official short-term memory.

"Hence the Government's attitude to Iraq: 'It won't hang around very long'. Rubbish. People haven't suddenly lost the ability to remember and to be affected by things for a very long time. The other cliché is that Iraq is only of interest to the chattering classes in London, as if no one else could be interested in politics. Again, rubbish."

Hitting his rhetorical stride now, Poliakoff continues: "One of my central tenets as a writer is that people are more sophisticated than they are given credit for.

"Millions of people have seen my last few works, and surely those dramas wouldn't have been that successful if people didn't understand them. Someone has got to explain why my dramas are successful if all TV is aimed at the lowest common denominator."

Although Poliakoff is far too subtle an artist ever to labour the comparison, in the film the public grieving for Diana clearly mirrors the private torture of Gideon and Stella.

A writer-director currently operating at the very top of his game, he explains that: "In the background, we have the public grief for Diana, while in the foreground we have Stella's grief for her lost son and Gideon's sense that he's losing his daughter."

But just why is that particular summer of 1997 such a suitable backdrop for drama?

"It was an extraordinary few months," the writer-director recollects. "The euphoria of the New Labour election victory on 1 May was followed by Diana's death, all the flowers in Kensington Gardens, and the amazing phenomenon of mass grief. It was the tragedy of the most beautiful woman in the world suddenly dying in a horrible way.

"Here was a young, posh, gauche nursery teacher who married into the Royal Family and soon became deeply unhappy and was possibly not treated very well. People related to her humanity - look at her compassion for people with Aids and victims of land mines.

"She was also an immense fashion icon. She was like the last silent film star; there is a link there with the public hysteria at the death of Rudolf Valentino. She had iconic status. Because Diana didn't speak, she could speak to everyone. Ultimately, it's a great story, one of the great stories of the late 20th century, and people always respond to great stories."

Gideon's Daughter is linked to Poliakoff's last film, Friends and Crocodiles, through the character of the gossip columnist Sneath (Robert Lindsay).

"Sneath straddles the two films," Poliakoff says. "I wanted a gossipy figure who could have known these people and who could make viewers think, 'Did Stephen Poliakoff hear this story?' He's like a sleazy version of Woodrow Wyatt.

"What also yokes these two films together is the sense of personal stories happening within a bigger historical framework. Without being schematic, I wanted to try to find out how we've ended up where we are today. I hope they're humorous, colourful, perky and vibrant."

In the end, Gideon's Daughter does not furnish viewers with specific answers; rather, it extols the supreme power of the imagination.

Brown declares: "It would be wrong to label Stephen's work as saying particular things. He shines a light on certain areas and makes you look at them in a way you hadn't considered before. It's up to you to decide what to think. He's very far from a polemicist. He's never preachy."

Poliakoff concludes:"All my films are about the contradictions of modern society. Whatever new rivulet of technology is invented, people will basically remain imaginative beings.

"One of the reasons certain things like The Da Vinci Code take off is because people want imaginative journeys. They respond to works that allow them to exist in their minds.

"As children, we all have dreamtime and everything that happens after that is designed to stop it. We writers are lucky enough to hang onto that childlike ability to live in our heads.

"What stops my work being bleak is that I believe that people are ultimately bright and imaginative. That's why audiences respond to it. The cliché is that British people are buttoned up, but we're capable of very powerful emotions and of expressing them in the most original ways.

"The older one gets, the more one realises that Charles Dickens was absolutely right: people are basically extraordinary.

"Western society is trying to deny that by making everyone buy into certain bullet points. That denial of people's imaginative capability is the main obstacle to progress. Gideon's Daughter doesn't provide any answers, but it does celebrate people's imaginative selves.

"That's what's so potent about television. It enters people's bloodstream. It comes into their living rooms, leaps out of the screen and surprises them. It can linger in people's imaginative memory banks for a very long time indeed."

Gideon's Daughter is a TalkBack, TalkBack Thames production, part of the FremantleMedia Group for the BBC.